Below is an excerpt from author Orland French’s book, PIONEERING: A History of Loyalist College (1992). While some references are no longer current, the publication provides a rich report on Loyalist’s history, which helps to contextualize its milestones. To read more from Mr. French’s book, please click here.

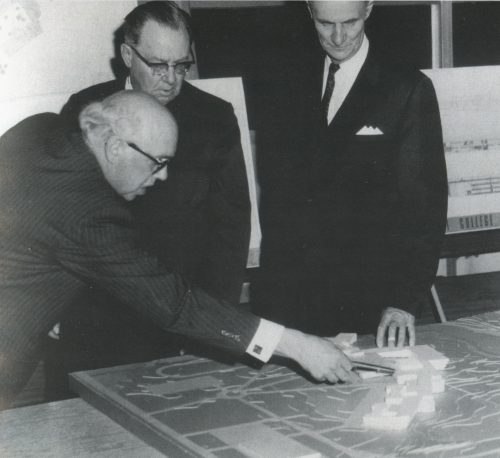

Planning the Kente Building: Architect W.E. Barnett, Loyalist Board Chairman Judge J.C. Anderson and president J. Kenneth Bradford

Lorne Johnston was a friend of Loyalist College even from the beginning. With sentimental family ties to the Belleville area, he had a special interest in seeing the Quinte Region acquire a college campus.

His efforts were acknowledged when the College officially opened. Johnston received the first honorary diploma to be awarded by an Ontario community college.

He had earned the tribute. After a career as a high school principal, Johnston had moved back to his home territory to work as a school inspector. But the bureaucrats called from Toronto to put him to work at the head office of the Ministry of Education, where he was eventually involved in establishing a system of community colleges.

Johnston was appointed Superintendent of Technological Training in 1963, just after Ontario had signed a deal with the federal government which would pour federal tax money into provincial training institutes.

There were institutes of trade, and there were institutes of technology, both jealously guarding their turfs. The Ministry of Education had other training projects in mind, and so it developed a new institute called a vocational centre. The name was a public relations ploy. “Parents were loath to send their children to trade schools, so we called them vocational centres,” said Johnston.

With a plethora of training institutes to handle, Johnston and other administrators devised a concept of combining several institutes into larger ones. It pleased William Davis, the Education Minister, who had hinted that he favoured the idea of junior colleges as developed in the United States. Yet when the proposal was outlined to him, the ever-cautious Davis said to Johnston, “I like the idea, but you’d better get it right.”

Johnston’s next task was to sell the idea to Cabinet. “We went to Cabinet and hoped we could sell the concept of building a couple of colleges – but we oversold the idea. Every Cabinet minister wanted one for his own area!” He added, “We were called back and told, ‘No, you can’t build one or two. We want to see a map of the province broken down into districts, with a college in each district’.”

Johnston and his department returned with a map showing 18 college districts. One was to be shared between Loyalist and Sir Sandford Fleming in Peterborough on a split-campus basis.

The cost of the colleges was to be absorbed over a number of years, but one incident almost staggered Provincial Treasurer Charles MacNaughton. When the Board of Governors of Humber College in Toronto unveiled its architectural plans for the college, the press asked, “How much is all this going to cost?”

The answer, “Fifty million dollars”, was reported in the newspapers the next day.

MacNaughton was told the costs would be spread over several years; he relaxed.

Several colleges, including Loyalist, started on the second floor of Centennial Secondary School; other colleges began in warehouses and other temporary quarters. Wherever the province owned technical institutes which were to be absorbed into the college system, the buildings and staff were turned over to the new administrations.